![]()

|

Index

•

|

|

Welcome

•

|

|

21st Century•

The Future |

|

World

Travel•

Destinations |

|

Reviews•

Books & Film |

|

Dreamscapes•

Original Fiction |

|

Opinion

& Lifestyle •

Politics & Living |

|

Film

Space •

Movies in depth |

|

Kid's

Books •

Reviews & stories |

|

|

|

|

The International Writers Magazine: Fiction

The Texas Long-Haired Rifle Association

• Jim Parks

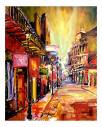

It took me a minute or two before I realized that Harry wasn't trying to pretend he didn't know me. He knew me once he got to where he could see me. The crowds passing by on Bourbon Street streamed around us on the narrow sidewalk. Some of the drunks shoved him and he struggled to remain standing.

He jerked his glasses off, tried to wipe them with a very shabby red bandana, and ever so carefully draped them back on his misshapen head. It was a head with a deep crater that ran the length of his part line on one side and there were wide, flat shiny scars that radiated out of a spot on his brow and through his hair on the other.

Harry’s glasses were bifocal, bent, smudged, chipped and sat askew on his head as if placed there by some absent-minded child with curls of greasy graying hair spilling over his eyes and the collar of his olive drab field jacket. He really was an absent-minded, childlike man wandering the streets of the Quarter like a stray dog, a piece of surplus war equipment. To me, he was a fellow Navy veteran, a shipmate.

He couldn't help the fact that as soon as he got a new pair of glasses they would get all bent up when he went into a gran mal seizure. They usually got thrown off his head. When he took them off and tried to hold them in his hand, they got all bent up.

We gave each other the secret Texas Longhaired Rifle Association handshake.

“They leave this stuff out here all the time,” he told me, grabbing a half-eaten hotdog in its little paper gondola and downing it in two gulps. “Can’t take it in the clubs with them.” He meant the tourists in their child-like quest to see it all, to see more, to rush from place to place with dollars in their hands.

There you had it, as far as Harry was concerned. He was a child that had stayed too long at the fair, lost his way and could no longer find his way out of the maze, enraptured by the bright lights, the crowds, the odors, the noisy frivolity of the setting.

I asked him why didn't come around the Avenue uptown any more. Why he didn't come see his brothers, just stayed around that old lame tourist trap like that? He ignored the questions, searching among the uprights of a little wrought iron fence. He found another half-eaten hot dog, this one with congealed chili on it.

He was like a scavenger fish on a reef eating the detritus of others’ feasting and disposing of the inedible.

He licked his fingertips in a dainty gesture that contrasted with his overall impression, that of a man so completely coated with the filth of the streets that you were sure he would have been unrecognizable to family and friends.

He downed a watery cola drink, ice and all, and placed the waxed paper cup in a convenient curbside waste basket that was emblazoned “Throw me somethin’, Mister,” the traditional cry of the Mardi Gras parade spectators begging for the krewe members on the floats passing by to throw them beads and doubloons. It was decorated in the Orleans provincial Mardi Gras colors of purple, gold and that funny shade of green.

He had a simple story, simple enough for anyone from our side of the tracks to understand. He had gotten injured severely riding a “Patrol Boat - River,” the Navy’s parlance for the PBR, a very rapid little fiberglass number with twin .50 caliber machine guns, plenty of rocket firepower, and the ability to stop in half its length or turn tail in the blink of an eye with its twin propulsion nozzles.

He received a small pension for what had happened to his head one sun-drenched afternoon in a Mekong River tributary as he toured Vietnam at government expense. “I have the Veterans Administration send the money to a bank account for my ex-old lady and kid,” he said proudly when anyone asked.

It had been like a cartoon, he would say. His war had been like a Technicolor movie only it had the logic of a cartoon, the kind that they used to show in matinees. Stuff like the Wile E. Coyote and the Roadrunner.

There were no heroics. He was lolling half asleep on the stern in the sun as the boat churned down the muddy brown stream. When she hit a mine, he got blown out over the water and he hit on his back. Just as he hit the water, a piece of the hull hit him in the head. In any other war, he wouldn’t have survived, but the medevac system, the Navy hospitals in Japan and California, and the medication enabled him to live in a perpetual state of fat Tuesday.

But nothing would stop the seizures. They came at any old time and he couldn't hide them.

No employer in his right mind would allow him to come on the job in that condition. It was just too dangerous in any industrial setting. In the service industry, it had a very negative impact on the company's image. It turned customers off.

When they found him beaten to death behind a dumpster near Canal Street - the result, they said, of a dispute over who could have a bag of unsold hamburgers left over at a fast food franchise - we of the Texas Longhaired Rifle Association went to the dime store and bought toy plastic rifles so we could drill over his grave in a lonely part of the Port Hudson National Cemetery a few miles north of Baton Rouge ninety miles west of the Big Easy.

We had all met in the neuro-psychiatric ward of the New Orleans VA Medical Center. All of our clique were from Texas, slumming in The Easy, hospitalized for one reason or the other in the ward where they treated nerve disorders and mental problems. Some, guys like Harry, had been long term residents of the domiciliary system because of their war wounds. President Reagan had cut the funding for those programs to the bone and they were now trying to make it in the normal world.

We had determined to keep our spirits up by getting little plastic toy guns at the dime store and drilling in the second line of the Mardi Gras parades, that raucous moving party that follows the parade from its starting point uptown to its terminus at the ballroom downtown. Funny looking street bums in filthy war surplus clothing sporting fierce looking little black plastic toy rifles, we sent Harry off with a twenty-one gun salute and joyfully upraised middle fingers.

“You know why twenty-one guns?” Fred David, Jr. asked the question as we rode along in Shorty’s old four-door Chevy with the expired Texas license plates. He fingered a knot the size of a walnut on the side of his head.

No one answered.

“It’s because that’s what seventeen seventy-six adds up to. Twenty-one.”

“Shut the fuck up, asshole.” Shorty blew his nose and repeated himself. “I don’t want to hear it. Shut up.”

He had one of those scars that start at about the eyebrows and streaks up and over the top of the head where a bullet hit his helmet and rocketed around inside its curved top.

He was crying softly.

He didn’t try to hide it.

© Jim Parks March 13th 2008

doverhalibut@embarqmail.com

More Stories

Home© Hackwriters 1999-2008

all rights reserved - all comments are the writers' own responsibiltiy - no liability accepted by hackwriters.com or affiliates.