![]()

Welcome • |

Lifestyles Archive • Politics & Living |

About

Us • |

The International Writers Magazine: Life Stories

• George Sparling

I jammed my eyebrows down, balled my fists, and threw some neat jabs at ex-boxer Dickie, my dad, who me taught me to throw punches like a man in the basement of our house. Headgear, big gloves, speed bag, big heavy canvas bag, punch pad, shoes: everything needed for him to stay in shape and for me to take out my aggression.

I jammed my eyebrows down, balled my fists, and threw some neat jabs at ex-boxer Dickie, my dad, who me taught me to throw punches like a man in the basement of our house. Headgear, big gloves, speed bag, big heavy canvas bag, punch pad, shoes: everything needed for him to stay in shape and for me to take out my aggression.

More stories

I quit my last violin teacher, telling my parents I was too talented for him but the real reason was he infected me with HIV. My CD4+ was slightly below normal range. It was the first time for me, and then during every lesson we did it. A neon sign, NO MORE SEX blinked on and off in my brain. I no longer thumped the speed bag. I’d get into the rhythm, allegro, fast as I could go, but not anymore. I left the speedy presto to Dickie.

I never told Dickie my former teacher infected me. If he knew he’d probably kill him. I take no medications yet; if the count lowers, then meds. I could get AIDS in a month, a year, ten years from now.

I practiced on my violin a seven-minute transcription of Richard Wagner’s “Liebestod,” its powerful love-death theme. Maestro demands a performance before accepting students.

“When’s the big date?” Dickie asked. “The one that’ll put you in the spotlight.”

“Saturday.” He looked serious, more than usual. “‘Liebestod’ taunted me as I

played. It’s all about death, the fear of death, but I like the challenge.

“Fighters sometimes taunted me in the ring, especially in clinches, but I overcame them, it made me fight harder, meaner.”

“The good old American self-help mania. Life’s one big Oprah Winfrey Show.”

“No it’s not. Life’s about heartbreak, and how to beat it with love,” he said, angry, pounding his fist in his palm. “Are you hurting, Carol?” he asked, voice softer, more like talking to Lana, my mother, who had taken my sister to visit her sister, a jazz pianist giving a concert back east.

“I’m not hurting. That’ll come later if the shit hits the shit.” I bent over with laughter, and he snickered.

“Good one. Shit always hits the fan. Keep your sense of humor and I won’t worry. Too much, anyway,” he said.

“In my mind I dance around the ring, keep the footwork going, until Saturday.”

“They’re thousands of Saturdays to go, every one the main event.” Dickie rubbed his calloused hands together. It sounded like sandpaper. “How’s fiddling going?”

“I listen to playbacks and they sound fine.” Actually, I’m not that good appraising my playing.

Damn, even though I’m seventeen I know Wagner’s a genius.

“What’s Maestro all about?”

“He’s well-known in Europe and Japan, and he’s had a handful of high school student prodigies. Some made it big in Japan.”

“I’ve seen Tom Waits sing ‘Big In Japan’ on YouTube.”

“Pretty hip for an old man,” I said, smiling. “You know another word for ‘cool’?

“What?”

“‘Sick’. Isn’t that sick?”

“You’re a prohibitive favorite for Maestro taking you and short odds you’ll beat the sick.”

He hugged me gently, backed away, and I said: “Never back up, you always said.

Move forward, aggressive beats passive.”

“It’ll be an unanimous decision with the ‘sick’” he said, going to the kitchen to eat quinoa, buffalo steak, with a large organic salad. His diet always mixed nostalgia and

contemporary health food.

He’d been down for the count sometimes but in the next fight he bounced back,

knocking out the same opponent.

After dinner, I slid Body and Soul into the computer.

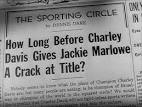

It starred John Garfield, a boxer corrupted by mobsters. Dickie praised the ring action. Garfield’s character, Davis, goes against the mobsters. Way behind on points, the last round sees Davis out for blood, banging harder than ever against his opponent, leaving no doubt who won the fight. His opponent was supposed to win. Afterward, Davis confronts his mob handler: “Get yourself a new boy, I retire.” The mobster: “What makes you think you can get away with this?” Davis refutes him: “What are you gonna do? Kill me? Everybody dies.”

“That’s positive,” I said of the movie. I unconsciously referred to my positive HIV test.

“Stop the sarcasm,” Dickie said. “That death dialog is just philosophy.”

He watched it again and I lay down on my bed. I’ve got to conserve my energy if I’m going to play Saturday. Baby steps, said Bill Murray in the movie What About Bob? Take life step by step. After an hour, I went downstairs. Dickie told me about a dream he had last night.

“I held your violin’s four strings in my hands after twisting the tuning pegs and

loosened the strings, pulling each through the hole in the tuning peg, unhooking the other

end from the fine tuner. My fingers felt the music you practice now.”

“How did you learn that?” I asked.

“I saw you do it many times, why couldn’t I.”

“Right.” I felt ashamed for asking.

“A man called Shadow threatened me. I grabbed the strings in both hands, raised my arms over Shadow’s head, and pulled down the strings around his Adam’s apple, yanked and twisted and pulled the aluminum strings until blood poured from his neck. He

slumped down, lying still, bloodied, and I decapitated him.”

Had he known about my last teacher, the infected one?

“But in real life you’re not threatened by anything,” I said.

“An opponent never intimidated me during fights, only when the referee raised his

arm did I feel threatened. Losing, it’s a mental condition, not a physical one.”

Dickie drove me to Maestro’s studio. He kissed my cheek, and said:

“I’m in your corner, loving you always.” He waited in the car, listening to a CD I gifted him on his birthday. Tristan and Isolde was one of many opera overtures he could hear.

Maestro had thick, white hair, and wore black tuxedo pleated trousers, and a Visconti tie-dye sport shirt. He was diminutive man, both less and more than I expected. It was his sharp face, his eyes, piercing and powerful. He tossed back his mane, and said:

“Whenever you’re ready, Carol. It’s your show.” Not one given to small talk. All I

said was, “Hello, I’m Carol.” A grand piano stood in one corner.

I took the violin from its case, and readied myself. It took ten minutes for me to relax and get comfortable. A meditative red and blue Rothko print hung near the piano.

Maestro sat on a black leather couch as I played.

He lay back, and fiddled with his groin. Playing “Liebestod,” he pulled down his

trousers and exposed himself. I wanted to flee, but, driven, finished. “How lovely that

was,” he said. “I was especially moved. The sex-death theme does that all the time.”

Maestro dispensed with a musical critique and walked towards me, his hard-on

flopping up and down, taking baby steps, unable to walk with trousers gathered around

his ankles. I stuck him in the eyes with my bow, then smashed the violin a few times

against his head until it broke. Bloodied when he closed in on me, I landed right and left

hooks to his face, not afraid to break his jaw and end my career with broken hands. I jabbed until his nose bled, more hooks battered his head, blood poured from above his eyes, blood streamed down the tie-dye shirt. I smashed his filthy gut many times.

“Ohh, Ohh,” he moaned, and I threw two uppercuts to his dangling balls. He backed away, but I pursued and smacked his jaw hard. He went down, his head hit against the edge of the large cast iron piano frame, then he fell to the floor, unconscious and bleeding. Dickie taught me more valuable lessons than any music teacher could.

I called Dickie on my cell.

“Maestro’s dead, I think. He came at me naked and I beat the hell out of him. What should I do.”

“Call the hospital, then 911. I’m coming inside.”

"I’m proud of you. He could’ve raped you, even killed you. Looks like a psychopath to me,” Dickie said when he saw the body.

“All music teachers look like psychopaths. That’s what art can do.”

The police came first, then the ambulance. The female Captain’s face scowled briefly.

“Is he dead?” Dickie asked. “I’m her father.”

“Looks like it,” a detective said. He looked at the doctor. “Yeah, he’s dead.”

Medics took Maestro out on a gurney.

“You’ll have to come in for questions,” a detective said.

“You’re not under arrest, and the chances you will be are virtually nil,” said the

Captain.

“You don’t need a cut man to fix up that fucker,” Dickie said. “Are you hurt,

Carol? If not, let these investigators do their job.” I wanted to be a single note from

‘Liebestod’.

“See my hands. They’re bruised some, two cuts on my knuckles.”

“The heavy bag toughened you up just enough but not so much as stopping your

violin from making beautiful music for the dirty fucker.” Dickie caressed my hands and

fingers, hugged me, not caring about the blood on my shirt. Maestro’s blood on Dickie’s

shirt looked like he had been in a fight with Shadow.

I soon got weaker, had an anal sore from a herpes infection, and grew feverish. The CD4+ was lower now.

I won the seven-minute round, an undercard or preliminary bout preceding the main event.

I would never be a headliner.

“They’ve been many long, slow counts by referees,” Dickie said. “They’re giving you one now.”

I never believed in God, but referees, them I believed.

© George Sparling Feb 2013

gsparling at suddenlink.net