![]()

|

•

|

|

|

•

|

|

| About Us |

•

|

| Reviews |

•

|

| Fiction |

•

|

| Travel Writing |

•

|

| Sport Comment |

•

|

| Lifestyle |

•

|

| Business |

•

|

|

•

|

|

|

•

|

|

|

•

|

|

|

•

|

|

| Archive 2 |

•

|

| January Edition |

•

|

| February Edition |

•

|

| March Edition |

•

|

| April Edition |

•

|

"Is God in?": Are Cathedrals built for God or Man?

• Nathan Davies

Among the many vague memories I have of visiting so called ‘places of interest’ as a boy, one that sticks out like, well, a pain in the ear, is an unplanned investigation of a relatively small cathedral in sunny Portugal. I say ‘relatively small’ in hindsight; to a twelve year old, it was huge, and that was the very first thing that struck me as my father and I made our way through the main doorway. Somehow the detailed, yet compact exterior, jammed between two less ceremonial buildings halfway along a broad yet busy city street, just did not correspond to the building’s interior. Everything, from the statues and windows down to the pews and doors was designed in such detail and to such a grand scale as to dwarf you. Even the air felt in some way oppressive because it existed largely above you; stretching away to a high vaulted ceiling that was simultaneously an amazing feat of engineering and a work of art. It was magnificent. It was terrible. It was awe-inspiring. And that wasn’t the half of it; everywhere I looked there was gold. At the altar, along the walls, the statues and inscriptions alike. Crosses, crucifixes, candlesticks, and almost all of the various other adornments that were not otherwise part of the architecture itself. I could not remember ever having seen a building like it before and was still trying to take it all in when my dad whipped off my cap and slapped me around the ear with it. “Show some respect,” he told me (although not necessarily in those words), “It’s rude to wear a hat in the house of God.” I had been so busy admiring the building itself that even with its icons and trappings I’d failed to see it as a church.

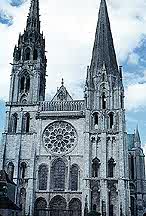

In these modern times it is all too easy to overlook the original meanings imbedded in the construction of our Cathedrals. Built mostly between the start of the middle ages and the end of the renaissance period, to the tourists, casual observers and even the academics of the 21st century they represent archetypal text book examples of period architecture more than they do monuments to God. I should imagine that few visitors to these imposing places of worship ever wonder at why many of the high, vaulted ceilings are constructed in a ribbed manner, or why, in the case of the Chartes cathedral in France, a square tower base should evolve into an 8-sided spire. Or even how it is possible to have such immense stained glass windows while still managing to support the weight of the structure itself (or why the windows should be stained at all). Instead, like my twelve-year-old self, most visitors are simply too much in awe of the effect created by all these things at once to stop to consider the effect itself.

When all the other layers of meaning are removed, that is what the great historical cathedrals of the world are all about: awe, and to inspire it in both congregation and visitors alike. They are designed to create such a presence as to dwarf and humble anyone who enters. Essentially, as houses of and monuments to, they are designed to the best imitations of God and heaven that the imperfect human being can create. That is why they had to be ‘impossible’. All that we admire in each of these buildings, the art, the craftsmanship and engineering, stems from reaching that goal. Take, for example, Notre-Dame de Paris. Begun in the early gothic style 1163 by then Bishop Marice de Sully it could not reach it’s full potential until after the invention of the flying buttress in 1175, as it was designed to take much of the pressure off the walls. Without such a device the walls would have had to have been much thicker and stronger, meaning there would have been fewer windows, and since the religion placed great emphasis on light as well as space in creating the desired ‘presence’, it was important to have a lot of windows. This came to be of even greater significance throughout the high gothic period as the taste for the gigantic passed into taller, more elegant designs which relied on decoration to convey meaning and lead to the wider use of geometric and allegorically patterned stained glass.

Ironically it is because these designs pushed beyond the boundaries of existing architectural techniques (and endured) to achieve a celebration of the Divine, that they, and the buildings which incorporate them, have come to represent a celebration of human achievement that has a potential to overshadow their original purpose in a practice that still exists today. Take Coventry for example. When the city’s second, and longest standing cathedral (formerly the church of St Michael) was destroyed by bombing during the Second World War, the decision was made not to rebuild the ruins of the old, but to instead construct a new cathedral alongside. In terms of design this could have been the perfect opportunity to break with tradition, to once again separate beyond doubt the significance of the religion that the building represents and celebrates from that of the workmanship that brought it into being. However, while the new structure acknowledges the spirit of rebirth and forgiveness that the clergy and the towns people found in the aftermath of the bombing, it, like its forerunners, was also made the focus of innovative engineering. In this case it was the subject of an architectural competition won by Basil Spence, for his mixing of old and new, in regard to both techniques and materials to reflect its place in a modern technical city. The new cathedral also attracted gifts of money and materials from as far afield as Germany, Hong Kong and Canada, and was adorned with various new works of art wrought in a contemporary style. So, by the very fact that it was conceived as something new and designed as a functional work of art, tradition was secured in Coventry.

In the New World, however, things are a little different, as America’s comparatively ‘young’ Catholic cathedrals are being given modern makeovers. These buildings which are, unlike many of their older counterparts in Europe, in comparatively little need of repair are being modernised to fit with the current ideologies of the state-side supreme church leaders. The concept behind the controversial renovating (or ‘ruining’ as many see it) of cathedrals in Milwaukee, San Antonio and Kentucky, among others, is nothing less than the restructuring of the church’s role within the community; trying to update its significance for a new age. In most cases the changes are alleged to deal with the internal arrangements only, leaving the actual architecture intact. However, altars are likely to be moved into a central position with the congregation seated around it (in, according to Milwaukee’s Catholic Herald, “community-building fashion”), and in at least one instance the baptismal pool will be relocated near to the entrance (effectively removing the function of one of the arms of the ‘cross’, the symbol on which cathedral floor plans are based).

Although such changes are not affecting the traditions of cathedral architecture as yet, there are serious implications for the future. Should this new community orientated re-designing overcome present criticism it could pave the way for new churches and cathedrals styled, if you like, in the absence of art and architecture. Cathedrals of the future could be religion orientated social (worker) offices so dedicated to the here-and-now that they become devoid of the history and that tangible sense something bigger than yourself, and that, in my opinion, would undermine the significance of the building. Religions need tradition to play off of, similarly, cathedrals need a certain degree of architectural design to create the right effect; it’s just a question of getting the balance right.