![]()

|

Index

•

|

|

Welcome • |

|

About Us • |

| Hacktreks Travel • |

| First Chapters • |

| Reviews • |

| Dreamscapes • |

| Lifestyles 1 • |

| Lifestyles 2 • |

|

|

The International Writers Magazine: Hacktreks in India with Betty Schambacher

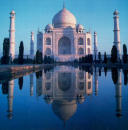

THE ROAD TO THE TAJ MAHAL

• Elizabeth Schambacher

It's 3 a.m. and the bedside telephone at the hotel in Bombay is shrilling a wake- up call. No time for more than quick showers before Bea, my travel companion, and I stagger bleary-eyed, down to the lobby where a small group of fellow travelers is gathering. No time for as much as a cup of coffee this early when even the Indian roosters aren't ready to announce the approach of another day.Fresh off a cruise ship, scarcely rested by a few hours sleep, we are bound for the airport and the 6:30 flight to Delhi, the starting point for our journey to Agra. The schedule is cruel but it is what it is; probably neither Bea nor I will head this way again. We can't pass up our chance to see the Taj Mahal.

Our Indian guide, cologne-scented, spruce in white pants and jacket, appears in the lobby. He greets us effusively, refers to a clipboard as he checks off our names, then satisfied that everyone is accounted for, leads us out to the parking lot where a green bus waits, motor idling. Even with a breeze blowing off the Arabian Sea, Bombay exudes the stench of dung and smoke. There's little traffic as our bus speeds through the dark streets, past blocks of decaying buildings; past rows of rag-tag shelters made of thatch, cardboard and scrap. I catch a glimpse of what resembles a bundle of rags lying against a wall – the bundle is a piece of discarded humanity, maybe alive maybe not, huddling a stone's throw from the guarded gates of an exclusive club.

At the airport, uncrowded at this indecent hour, we board an Air India flight to Delhi, two hours away. Female attendants, colorful as butterflies, caste marks matching the jewel colors of their filmy saris, serve a breakfast of a chapatee, eggs floating in a brick red sauce, something I can't identify. I manage no more than a mouthful. Our guide, who sits beside me, observes my reaction to the menu with amusement. He is a handsome fellow, eyes like damson plums, lashes a dense black fringe. He finishes his breakfast with what I suspect is exaggerated relish for my benefit, then lifting his eyebrows in a question, motions toward my virtually untouched tray. I surrender it gladly. He polishes off everything.

He wants to chat. In flawless English he tells me he is married, that his wife has lately given birth to their first child. "But it is only a girl." He sighs dramatically, looks at me with a sly smile. I shrug. It is too early to rise to a bait, especially a sexist one. He tells me his name, which I can neither pronounce nor remember. "Call me Johnny," he says. "That will do. Johnny."

At the moment I do not care to call him anything. I am weary and want to sleep but I cannot. Bea, seated in the row in front of me, has drifted off and I regard her with envy. She can sleep anywhere. I am distracted by the attendants who flutter along the aisles, offering sweets, newspapers, muddy coffee. The plane shudders and the "fasten seat belt" sign goes on.

The plane plunges, bucks like a steer. I have to pee. Johnny pats me companionably on the knee in a gesture of reassurance. My nerves must be transparent.

"We will soon arrive at Dehli," he promises. "This flight is very short." He says a bus will be waiting to take us to Agra, a five-hour drive that he assures me I will remember until I am an old woman. I tell him I am already an old woman and he shakes his head, looks at me with pretend disbelief.

He is a flirt.

We land and file from the plane into the Delhi morning. Our small band sorts itself from the other passengers and we gather around Johnny who herds us to a waiting bus. Now wide awake I take my first real look at our traveling companions: A lanky middle-aged German accompanied by his grown, red-headed daughter, a large young woman with thick legs and short skirts; an older couple, the husband reminding me of a stand-up comic from the Borsch Belt. (Later I learn this is, in fact, the case. He is retired from show business; his name is Morrie.)

There are other couples in our group. I observe one woman, much too thin, her skin assaulted by age and sun. She looks disgusted. Her voice is loud and gravely, she carries on a litany of complaints: the air turbulence during the flight, the breakfast, the condition of the bus, her seat. She complains about India. Her husband ignores her.

Johnny has been lured into the front seat where he lounges with a good-looking, fiftyish woman whose name is Jean. She has the air of a businesswoman with a lot of money; she is a take-charge type. She has an eye for Johnny. This offends me because now I am obliged to take the only vacant seat which is across the back of the bus. It is over the wheels; it is hard and uncomfortable. I consider it Johnny's responsibility to sit here.

The bus rattles along and soon we are on the highway to Agra. It is white-knuckle time – for the passengers, not the driver, who maintains his cool through hours of threatened highway carnage. Buses, passenger cars, bicycles, mopeds, wagons, cows – they stream along the road, hell bent for destination or destruction, whichever comes first. It becomes clear that the one piece of essential equipment on an Indian vehicle is the horn and the one on our bus blares in constant, ear splitting counterpoint to the rest of the road cacophony. Shouting to be heard, Johnny turns to inform his flock that while most countries specify right or left hand driving, in India the choice is optional. Nor is it a choice to be made in haste; in the matter of right-of-way, drivers do not rush to judgement. The practice is to tromp on the accelerator, aim, and should another vehicle have chosen the same course from the opposite direction, wait until the final second to veer to the side.

Bicycles and mopeds flee from the highway to the safety of a road shoulder and back again to the highway.

Time after time we pass some manner of conveyance which has broken down with one problem or another. A wagon with a crumpled wheel, a battered pick-up with steam pouring from the hood, a moped lying on its side, the driver and passenger gesticulating in the middle of the road. I count two dead dogs and several inert chickens. Taking suicidal chances, drivers weave through the horrendous traffic, sometimes on the road, sometimes not on the road; sometimes up to our back bumper, sometimes threatening to become our hood ornament, depending on the direction they're traveling. The bus echoes with hissing breath intakes and murmured asides to the Deity as we hurtle along, going with the flow.

There is no open country but rather a succession of villages and larger settlements, all screaming of poverty. A pall of smoke hangs in the air and I see a group of children occupied with patting dung into the blocks which will be dried for use as fuel. There are cows, many cows. They amble where they choose to amble, or remain in the middle of the road if that is their preference. Johnny explains that they may or may not have an owner. Many have simply wandered off to fend for themselves but in any case are treated with respect, endowed as they are in India with certain, inalienable rights.

At one point we come upon a large herd of humped Brahmin cattle accompanied by shepherds, plodding along the side of the road. We are told they are heading for auction in a city miles away. We continue to pass a succession of small enterprises housed under thatched shelters propped up by wooden posts. Customers mill about at roadside eating places where long tables are set up in the dirt.

Not surprisingly, business appears to be brisk at the numerous automotive repair places and makeshift garages, all identified by a frontal sea of rusting chassis and strewn car parts. The bus stops for what Johnny tells us is a "photo opportunity." The driver has pulled off the road in front of a native market, which is exotic, but too teeming with people to ensure any picture other than a study in heads and backsides. We are starting to move away when the driver jams on the brakes and we rush to expend film on a snake charmer who has planted himself at the curb. He pipes an eerie treble for an obliging, undulating cobra.

More such photo opportunities lie ahead at the promised rest stop, a posh tourist resort a few miles off the main road. We drive through lush, manicured grounds, blazing with flowering plants, cascading fountains and topiary, to the entrance of a sprawling, pink lodge.

There's a mass exodus off the bus as we all make a beeline for the facilities. Urgency gives wings to my feet and I gain on the rest of the pack to claim a vacant stall, with an Asian toilet, in the women's room. At this point even a tiled hole in the ground is welcome. The place reeks and I do not care. When I emerge, Jean, the woman who sits beside Johnny, is acquainting the wife of Morrie the comedian, with the technique of using a non-Western W.C.

She demonstrates by dropping her slacks and underpants to her thighs. She leans forward, grabs a handful of the waistband and the crotch, then stretches it out in front of her. "You must bend far over," she instructs. "Feet well apart so you don't pee on your shoes." Her student looks doubtful. She is intimidated by the plumbing.

The red-haired German girl, who is waiting for a vacant cubicle, contributes a piece of valuable advice. "When traveling in Asia," she says, "it is good to have on a skirt. Never wear a jump suit." The constant complainer emerges from a stall. As usual she is scowling and does not speak to any of us. My hope is that she peed on her feet.

Johnny has given us a half-hour before we must return to the bus and I wait for Bea to emerge from the toilet. A dedicated shopper, she wants to visit the gift store so I leave her and set out to explore by myself. Landscaping artistry has been lavished on the grounds but since the woman's room could have seen nothing resembling a sanitation inspection since God knows when, the resort is mostly façade. It remains a fascinating place. I hear a small commotion and fish out my camera in time to snap a picture of a bedecked elephant swaying down the path, four giggling Indian children hanging out of the howdah. I catch a glimpse of a camel loping through a copse of trees. The rider appears to be no more than ten years old.

Farther along I encounter a monkey, tarted up in a green velvet jacket and cap, being put through a routine by its trainer. I am reminded of ChiChi who a long time ago performed nightly turns at an open-air photo gallery in Los Angeles Chinatown. It all seems very far away. A white cat minces along the path in front of me, directing my way to the parking area where I join members of our group. They are watching another snake charmer do his thing. I snap a picture and gingerly toss him some rupees, afraid to move too close to the cobra lest it take a fancy to some part of my anatomy. The man scowls and gestures for more.

Confused, I reach for my wallet, but Johnny, who has been watching, shakes his head at me and takes my arm. "You gave him more than he makes in a week," he says. "We can't spoil these people."

Slowly the bus fills, Bea bringing up the rear, beaming and carrying a plastic sack. As soon as she sits down she pulls a black sequined vest out of the bag and holds it up so I can see it from my seat in the back. It is very pretty. She will never wear it but she derives pleasure from the search.

We are not far from Agra and the prospect of lunch inspires me to pray harder that we will not be spattered along the highway but will reach our hotel with body and soul intact. In less than an hour we arrive. The hotel appears to be well enough and we are surprised to hear that our rooms are ready. We are told that the view of the Taj Mahal from our window is spectacular but a haze has come up and we can't see anything. So we wash and go back down stairs where a line has formed at the buffet table. Bea and I fall in behind Morrie and his wife; in back of us is the woman I have designated as Mrs. COB, which stands for Complaining Old Bat. She is in her usual form, carping about whatever displeases her at the moment; her husband, also as usual, is silent. The food displayed is not particularly Indian – meat patties, rice, macaroni, some kind of stew, a tray of assorted relishes. When I hear Mrs. COB gasp, I turn around to see her pointing to a cockroach which peers over the side of a stack of plates, antenna waving. "Terrible!" She shudders. "Terrible!" She makes a strangling sound. Morrie glances at her, observes the roach.

He grins. "It won't eat very much," he says cheerfully. She makes another strangling noise and leaves, her husband trotting behind her, shrugging as he goes.

The sight of the roach has not endowed me with confidence in the buffet, but I am starving to death and so is Bea. We pause, confer, and give up. "What the hell," says Bea.

We find plates from another stack and select a little of this and a little of that. We examine each forkful. When lunch is over we return to the bus and endure a brief ride to at last gaze upon the Taj Mahal, that monument of perfection, that spiritual tribute to a mortal woman. Our first vision of this wonder lives up to everything we have read and heard. It is spectacular. It is unreal, its magnificent marble image mirrored by the crystal water of a reflecting pool. We are entranced. We grow lyrical as we regard this architectural marvel, choosing for the moment to forget that it's a mausoleum, commissioned by the philandering Shah Jahan for his patient wife who had squeezed out fourteen children before giving up the ghost. Both the shah and the missus are entombed in the Taj Mahal.

We have a special guide who leads us up to the main entrance, bypassing a line of waiting people that extends farther than we can see. We crowd inside and are plunged into darkness. There are no windows, no lights. A large hole in the floor just inside the doorway is covered by a sheet of plywood and I manage not to trip over it. We become part of a solid phalanx of bodies that shuffles along aiming for the twin tombs that occupy the center of the temple. It is black as a pit. Guides hold flashlights to orient their respective flocks.

It is hot. It is airless. It stinks. A turbaned Sikh eight feet tall tramps on my foot. A group of schoolchildren plows in front of us while our guide is demonstrating the translucence of the marble tomb by shining his flashlight on the surface. I cannot see him; I cannot hear his explanation.

The experience in the inner sanctum of the Taj Mahal is not great.

Bea, who is wiser than I am, or perhaps clairvoyant, has chosen to skip the tour and enjoy the scene from the vantage point of a marble bench beside the reflecting pool. She has made the acquaintance of an Indian family and has spent the time chatting. She is rested and cool. After the members of our group surface, we are lined up for the compulsory photograph, the Taj Mahal in all its pictorial, pristine glory serving as a background. We can now prove to anyone who cares, that we were there.© Betty Schambacher November 2004

schamb at eburg.comYemen

Betty Schambacher

More World Destinations

Home© Hackwriters 2000-2004

all rights reserved