![]()

|

Index

•

|

|

Welcome

•

|

The International Writers Magazine:In Ruins

SOCKBURN Not in the Lake District

• Clegg Jenkin

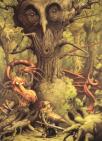

A now crumbling early nineteenth-century mansion in a veritably Brontë-esque location, nearly encircled by a sluggishly flowing river, banked with giant hog-weed and backed by tall trees; a legend of a medieval Lord of the Manor slaying a marauding dragon; the stone under which the dragon is supposed to be buried and the trough which the locals used to fill with milk to try to appease its gargantuan appetite still visible (with some effort).

A ritual greeting for each new diocesan Bishop with the falchion (now in the Cathedral Treasury) said to be the weapon that slew the dragon; a farm house where the poet William Wordsworth lodged for six months in 1799 and courted his future wife, Mary Hutchinson, where Tom Hutchinson, Mary’s brother, once bred a seventeen and a half stone sheep and where the already-married Samuel Taylor Coleridge fell in love with their sister Sara; a ruined sandstone church with an important collection of Viking carvings where a Saxon Bishop was crowned, and which features, together with images of the dragon, in Coleridge’s poem Love, inspired by his feelings for Sara; a deserted village by the vestigial remains of the earlier, crenellated medieval manor house.

And in the next-but-one village, the church where Lewis Carroll’s father was rector and where the legend of the dragon inspired the young author to compose the "Jabberwock" poem in 1855.

The place, NOT in the Lake District, is in fact Sockburn-on-Tees, on the other side of the Pennines, about six and a half miles south of Darlington in County Durham, a dead end at the very bottom of a long, narrow meander in the aforesaid river, (check the OS map), accessible only by one long, thinly-populated lane. Accessible in theory, for the lane is blocked by a gate some way short of the old settlement, with an unwelcoming "Private" notice on it, whence neither the hall nor the farm-house is visible. The motorist has to reverse his car and return by the way he came; the pedestrian can take a footpath over a field and cross the river Tees by a footbridge some distance from the hall.

There is evidence of Roman activity in the area. Sockburn must have become a very important Christian centre, for records show that one Higbald was crowned Bishop of Lindisfarne in the church in 781, and in 796 Eanbald was made Archbishop of York. For centuries, the estate was in the hands of the Conyers family, and it was Sir John Conyers who reputedly slew the dragon, which had been terrorising the neighbourhood, consuming cattle, sheep and humans with equal relish, some time in the thirteenth century. It is recounted that Sir John prayed all night in the little church for victory over the dragon, and even offered to sacrifice his son. After a terrific battle next day, the dragon was duly slain. The locals dug a hole, buried its corpse, and put a huge stone on top. "Grey stone" is still marked on maps today. The stone bears a crack where a farmer in the nineteenth century is said to have tried to remove it with explosives – to no avail, and although it sits on some of the most fertile soil in the country, no-one else has succeeded in removing it, or seeing what’s underneath.

The falchion, now in Durham Cathedral Treasury, is dated by experts as being a little later than thirteenth century, but it’s a rare survival nonetheless, and contributes to a good story! There are several other dragon/wyvern legends in County Durham – a little further north near Durham itself the "Lambton Worm" still features in a song. One suggested explanation for the Sockburn dragon is that it harks back to a Viking raider in the area who was eventually defeated; another is that families who were granted land liked to have an heroic ancestor, to justify, at least in part, their entitlement to that land, and so they concocted a suitable legend.

For many years, the falchion was kept in Sockburn Hall. Sockburn being the most southerly point in County Durham, the falchion was ceremonially presented by the Lord of the Manor to each new Prince-Bishop of Durham as he entered his diocese for the first time at the near-by bridge at Croft-on-Tees, with this formula of words: "My Lord Bishop. I hereby present you with the falchion wherewith the champion Conyers slew the worm, dragon or fiery flying serpent which destroyed man, woman and child; in memory of which the king then reigning gave him the manor of Sockburn, to hold by this tenure, that upon the first entrance of every bishop into the county the falchion should be presented."

The practice died out in the early nineteenth century but was revived again when David Jenkins became Bishop in 1984, the Mayor of Darlington rather than the Lord of the Manor doing the honours. Bishop David is said to have waved the falchion round his head and promised to fight the twin evils of poverty and unemployment!

The Conyers family died out in the seventeenth century, and the original manor house fell into ruins. In 1670, the estate came into the hands of Sir William Blackett, a Newcastle industrialist and minor member of the gentry. The farm-house where Tom and Mary Hutchinson lived was built in the late eighteenth century, but it wasn’t until 1835 or so, that the still standing hall was constructed. In 1838, the historic All Saints’ church was closed and allowed to become dilapidated – literally, for some of its stones are said to have been used for road building, - and a new church with the same dedication was built across the river at Girsby, all at the instigation/expense of the then occupant, Sir Edward Blackett, who presumably wanted a fashionably picturesque ruin near his new mansion. It has been suggested that he removed the few villagers away at the same time, and sources also indicate that Theophania Blackett (relationship with the above yet to be established) built the footbridge some way north of the hall and provided the footpath across the field to it in 1869 or 1870 in order to avoid having the locals use the ford located near the house to get to their church – late examples of land clearance.

The hall is still in private ownership and in great need of restorative attention. A few years ago, the National Trust and English Heritage were said to have expressed interest in it, but it would require the spending of several fortunes to restore it to any glories it may once have had. Archaeologists ought to be let loose on the site of the original manor house and village, and the ruined church (predating the Norman Conquest by nearly three hundred years, don’t forget) should be properly in the care of the diocese. Little encouragement for either of these aspirations seems ever to have been forthcoming. This is a great shame, for such an at one and the same time eerie and romantic location with so many religious, legendary, historical and literary connotations deserves to be widely known. The associations with Wordsworth alone would have ensured it of this, if it HAD BEEN in the Lake District.

© Clegg Jenkin Feb 2006Clegg Jenkin is a local historian who lives in the ancient lanes of Southsea and rarely sees anyone.

Hacktreks a world of travel destinations

Home© Hackwriters 1999-2006

all rights reserved - all comments are the writers' own responsibiltiy - no liability accepted by hackwriters.com or affiliates.