![]()

Index • |

Welcome • |

About

Us • |

21st Century • The Future |

World

Travel • Destinations |

Reviews • Books & Film |

Dreamscapes • Original Fiction |

Opinion

& Lifestyle • Politics & Living |

Film

Space • Movies in depth |

Kid's

Books • Reviews & stories |

The International Writers Magazine: Nigerian Law

Musin: To Live or Not, To Leave

• Lakunle Jaiyesimi

Choosing a home has lately constituted, for me, a dilemma. The dilemma, I must admit, is a sweet one. It obviates any possibility of boredom, even in its most stagnated form.

After many searches, it came to appear that the search itself was the end; the roads became the home. But finally, my interest was heaved towards a home (a room, precisely) that would stare me in the face as a cosy, non-ventilated spacelessness (an unfortunate killer of

inspirations). It was located in the heart of Mushin. That’s the spelling afforded by the developing civilization of a quintessential Nigerian town originally named ‘Musin’.My return journey to contemplate the idea of living in the area brought me skin-to skin with a juxtaposition of the extralegal and the legal sectors (or rather, a coexistence). But all the same, it was an interesting experience to have a first-hand knowledge of it all.

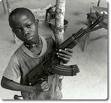

There was this hue-and-cry that instantly gathered the stench, the sweat, and the ugliness of unkempt bodies. The crowd constituted young boys and girls. Most were obviously malnourished, tattered, edgy, reactionary, bony framed, soot-faced, and callously friendly. The boys brandished assorted guns with a skill that would have been envied by returnee-soldiers. They were in control of the neighbourhood. The others (who could have been saner) regarded these boys with awe, and they treaded with caution.

A little receded from public glare, there was a group of black-uniformed policemen. They would never wish that the boys discovered their identity. Inconspicuously, they brandished their guns; and maybe even shammed the guns to be mere logs. They controlled – or they seemed to do so – a traffic of less than 3-cars-in-3minutes. It was common-knowledge that they usually evaded the heavy-traffic roads, except the brave ones within the ranks. Here they were, removed from the larger society, where the world needed them most, and yet here, forced to observe the routine of uselessness.

Funny though, my curiosity could not have been less astounding when I caught the supposed policemen also regarding the gun-carrying boys cautiously and with some trepidation.

Who actually is the law-enforcer here?I moved on, anyway, away from the ridicule of the legal structure – or what some may prefer to compound as superstructure, maybe. But alas, that proved not to be the last.

The traffic was heavier at a point, and yet again – though surprisingly – there were policemen. These made fewer attempts to conceal their identity, not that they were proud of it anyway. But it appeared they were in the midst of an equally embarrassing situation. The policemen were fussing. A duo – scary faced boys – squeezed some notes of naira in their tough-muscles-lined hands and retrieved more from the bus conductors and drivers, who prudently doubled as their

own conductors.It was at these extralegal boys that the legal policemen directed their fuss. “How dare you?” one legal law enforcer cum naira-extortionist inquired of the extralegal law enforcers cum

naira-collectors. “How dare you collect money on our behalf?”If I tell a lie, let the rains beat me a day after. “How dare you use our presence to enrich yourselves, while we get nothing?” The policemen, passing the statements from one to the other, were near tears. They had their voices reverberating like the angry thunders of

early spring. They sounded cheated; appearing as victims of fraud.But one quickly wonders, “Who cheats who? Who defrauds who?”

It probably brings us to the question of the extralegal overriding the legal; the legal being at the mercy of the extralegal. And the legal almost becoming the extralegal; making even legality extralegality.

I wish I could here expatiate on the face of the naked matter; how the issue of segregation and legal inconsideration come together to amass a wealth of extralegal subjects in the community. We probably might need some schooling stint at Osodi, Musin, Akala, Ladipo, Empire and

such places to better appreciate what the implications are making laws (more, it’s an adaptation of foreign laws) without considering what the majority of the people are able to ever comply with. The fallout of which is a continued precipitation of crime, crime and crime.All may now hail crime (It’s only an official pronouncement), I suppose.

© Lakunle Jaiyesimi Feb 2010

lakunlejaiyesimi@googlemail.com

More Comment