![]()

Welcome • |

About

Us • |

The International Writers Magazine: Hacktreks in China

• Tom Clifford

Guilt is a terrible thing to bring to a table. For hours our small bus had been buffeted by nature’s wrath, exposed on Guizhou’s mountain passes and only the dexterity and skill of our driver kept us this side of paradise.

Rain slashed our windows in a Hitchcockian shower-scene frenzy. Our schedule had been literally washed away. Up through gorges, down into valleys, tight bends, narrow roads, white knuckles. Then relief as we descended to the flatlands. We were in Buyi country and stumbled upon a village Yinzhai, nestled under mountains. A vision of tranquility. Still far from our eventual destination, we craved rest and nourishment.

Our arrival was unscheduled, only the gods could have known, but the choice of this particular village, just after 7pm, turned out to be divinely inspired.

“Can you feed us’’ shouted the driver to a woman in the village kitchen.

“How many?’’

“Eleven”.

“Twenty minutes. Have a walk, see the village, relax,’’ came the assured response.Darkness, as if reluctant, had not fully descended as the remains of the day saw nature exhausted by its exertions. Like us, the countryside was breathing a sigh of relief. Mountains looming over us now appeared picturesque. The sky streaked with red hues, no longer in torment, seemed to be blushing with embarrassment at its previous behavior.

Wits gathered after a short walk, we headed for the meal but first acknowledged an old discolored poster in the main village home displaying the core principles of the Buyi ethnic group. Heaven, Earth, Emperor, Ancestors, Teachers, it read. History was giving us the privilege of tapping us on the shoulder before we sat down to eat.

Fried fish, pork, vegetables of blazing color were offered with joyous abandon to shouts of appreciative approval. All prepared, cooked and presented within 20 minutes. And then the guilt. Had they enough food for the village, were we eating them out of house and home? We were assured that the village stored its food for months in advance and had more than adequate supplies. On hearing this, pangs of hunger overran the scattering forces of guilt and a white flag was waved from the ramparts of doubt. Not a word was spoken for six minutes as stomachs were replenished and the body sucked nutrition from the offerings.

Our thanks, given with the contentment of full stomachs, were accepted graciously as the plates were cleared. An unqualified act of generosity had been executed. We had been recipients of a kindness to strangers. Outside, darkness had finally overcome its inhibitions and descended, ushering in a time for reflection.

For days we had been traveling through the highs and lows of Guizhou province. Its fertile soil struggles to produce on mountainous terrain but when given a chance on the horizontal it can provide a vertical harvest for the imagination. Nothing, it seems, is beyond its capability. The usual suspects, broccoli, corn, are grown but so too are delicate leaves for tea, tobacco and chilies to jump-start the synapses.

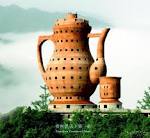

Hours before our nighttime feast we had seen May’s darling buds herald the start of teatime for the pickers and saw firsthand, literally, the lengths some people will go to for a good cuppa. As we walked the hills and talked to the pickers I experienced a coffee mourning. The bean has been vanquished from sight and site by the leaves rampant. No café lurks within a radius of 25 km, I was told. An exaggeration perhaps but its presence would seem incongruous, like a thick woolen jumper on a Beijing August day. Time to turn a new leaf. This is Guizhou tea country. If in doubt look to the heavens where a laser beam cuts across the clouds from a giant teapot that dominates the nearby town of Meitan’s skyline.

Tea, especially green tea, is growing in popularity; you could say it’s a top pick. China exported about 300,000 tons of tea last year, 30 percent of it green.The art of picking tea is almost as sublime as its taste and requires a surgeon’s delicacy and optical prowess.

“You can never use your nail or sharp edge like a knife,’’ one picker said. “If you do, you cauterize the cut and it turns black. Each leaf has to be torn, delicately, from the plant.’’

This is no job for the faint hearted. Sweltering sun, torrential rain, the body poised to strike and then tear the fragile leaf for hours on end. Perched on mountainsides, this may be a job with scenery to die for but it asks a back-aching price.

Guizhou’s mountains stand sentinel, guardians of a beauty still unveiled to mass tourism. This is China, but not as many know it. In rural parts of the province, far from the madding crowd, the three S's , sight, smell and sound, ravish the senses with a ferocity of lovers reunited. Tea country has a more subtle, enchanting, allure. The rolling hills are not awe-inspiring like the mountains but they are easier on the eye and provide a gentle introduction to heights of amazement further down the road.

The picking season is April to October and each plant will produce a new leaf every two weeks or so.

After picking it is allowed to dry naturally for a few hours, then it is stirred, not shaken, mechanically to give it shape before being shaken to dry it further. After this, it is rattled in what looks like a cement mixer to enhance its flavor.

Packaged and of it goes for a shelf life before floating invitingly in a cup or glass.

Tea has a special place in Chinese and world history but only now is green tea getting even a fraction of the global publicity it deserves. I am a coffee lover but there are times in the day when I could be unfaithful to the bean, especially in the restful hours after 6pm when green tea would settle the frayed nerves of a hard day’s night more than coffee. Reflections over, we rise, with sighs of satisfaction, from the table, sustained for the night’s challenges on the road under stars that would have inspired Van Gogh. The following day, in bright almost apologetic sunshine, our plans were back on track. We traveled to a papermaking village, cradled by steep granite gorges. For 600 years the village of Bai Shui He has been cutting and striping bamboo, mixing it with plum juice, pulping, hanging and drying it out. The paper for ancestral offerings can also be used for calligraphy. It costs 12 yuan a kilo. Nature’s bounty.

Then onto a nearby Buyi village that was expecting us for a meal. No guilt here while we hammered the rice, as if it was trying to emerge from the underworld, into a sticky substance, which was then peppered with seeds and eaten in small handfuls. Maidens fair, in traditional blue costume, offered us rice wine and food. We drank, they sang. This side of paradise? The lines were blurring, we may have stepped over. Tiny cups were raised to lips and then turned upside down to show that no alcohol remained. Both a tribute and a delightful challenge. The table was not just groaning under the weight of food but begging for mercy, pleading for us to lighten its load. Laughter competed with birdsong. More maidens singing, more rice wine. Well into the night we stayed, unable to pull ourselves away from the gravitational pull of incredible hospitality.

The hour of departure could no longer be denied. Farewells were exchanged with a solemnity that contradicted the previous gaiety. Handshakes seemed inadequate. Full body hugs and claps on the back were called for. Journey’s end had been reached. Until we laugh together again, paradise postponed.

© Tom Clifford December 2013

cliffordtomsan@hotmail.com

* Reprinted from the China Daily