![]()

Welcome • |

About

Us • |

The International Writers Magazine: A Greener Globe

• Amy Siqveland

Though I’m not one to usually laze around on the beach, with so many below-zero days this winter in Minnesota, I can't deny that I missed going outside. That is why, when I was informed that I had a won a “free trip” to a “wellness sanctuary” in Antigua, I was ecstatic to be able to defrost.

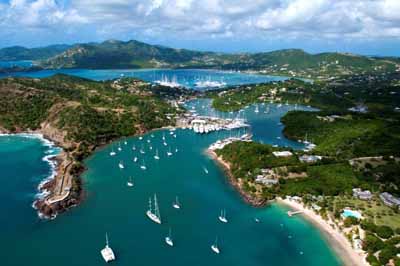

No matter how you look at it weather-wise, the Caribbean is pretty much the opposite of the upper Midwest United States in the winter, with its tropical breezes, lush foliage and stunning vibrant colors. The atmosphere is relaxing and carefree and, to be honest, I was initially just excited to ditch my vitamin D prescription and get my body back in balance.

It was amazingly easy to embrace the “slower lifestyle” and tranquil turquoise waters, to say nothing of the streams of ripe fruit, fresh seafood and nutmeg-frosted drinks. It was also obvious how simple it would be to bury one’s toes (and head) in the warm powdery sands like an ostrich and not look too far beyond what and how one was being served.

As I was a guest of a Green Globe Certified commercial establishment whose mission endorses the Ceres Principles (which tout ethical and environmental responsibility in business), I had no reason to doubt the company’s ever-present assurance: everything I needed to create my own “personalized version of paradise” could be directed by the “ever-obliging” staff. And, if I didn’t want to, there certainly wasn’t any reason to even leave the all-inclusive boutique.

Those who struggle with rosacea are not really suited for sun-worship, however, so it wasn't long before I was burned and noticing certain tensions blazing beneath the surface. At this point, I was more than ready to get the real scoop…and venture beyond the spa’s doors.

My fiancé and I ended up renting a car and, on our journey around Antigua, met a number of locals, some of whom welcomed us into their homes. In these places, while enjoying Rastafarian music and political programs from the opposition party, we heard more about how the luxurious resorts (and incessant party culture) have created some pretty serious challenges for the people who live there.

On various stops we learned about the endangered and extinct animal and plant species; the coral reef degradation; and the ways people here have been put at risk due to faulty wastewater management. We were surprised to find out that there is not currently a centralized sewer collection and treatment system and some sewage is still being buried in landfill pits near wetlands. A high percentage of hotels have on-site plants at this point, but partially treated sewage is still being dumped into the sea.

With each stop, the juxtaposition of wealth and poverty became more pronounced and the lines between past and present “criminal” and “legal” activity more blurred: all this intense beauty set against a garish backdrop of still-celebrated colonial remains.

The relationship with the natural world in this country has such an important bearing on everyday life where droughts, hurricanes, tropical storms and climate change constantly carve out the fragile landscape. Natural disasters have caused millions of dollars worth of damage in the past, significantly affecting homes, employment, livestock, vegetation and mobility. Living with this constant threat of terrain reorganization and crisis amplifies the vulnerability of this small island. It also stresses the importance of allocating reserve funds to the areas of prevention, sound design and stewardship.It is not only weather that has modified Antigua’s topography but other external forces too. When the British arrived in the early 1600s, much of the island was cleared to establish plantations to mass-produce sugarcane. A number of people were then brought in from Africa and various islands in the West Indies to work as slaves on these estates. With this change in demographics, new power structures were introduced, as well as a myriad of natural predators and diseases.

With the abolition of slavery and, later, the country’s independence, the plantations slowly closed. Demand for sugar was then met in new markets since the cost of production had significantly increased. Years of non-residential land ownership and financial jurisdiction continued to morph the nation’s direction, however, as the slow trajectory, from a locally run agrarian and seafood community to the overseas-managed service economy it is today, was already years in the making.

These gradual alterations in agriculture and the robust foreign development of coastlines have led to many of Antigua’s current problems, including acute soil erosion, contamination of buffering mangroves, incomplete protection of forest reserves, pesticide pollution, sand mining and overfishing. The lack of local investigative and regulatory council in many of the tourism boards stems directly then from a set of inherited beliefs and practices that still support a hierarchical format of racial stratification.

What was most interesting in listening to the varied accounts on this trip was the extreme contrast in how the valued natural attractions were being marketed by the people who grew up in Antigua versus the agencies targeting tourists. And how, in response to what seemed like pretty incompatible viewpoints of “growth” and “progress,” acts of resistance to colonialism are still very necessary today.

Capitalism, globalization and even current notions of progressive imperialism have stepped in where colonialism supposedly ended and continue to manipulate the current political administration and diplomatic relations abroad. They dictate how the land is divided in the face of competing interests, how corruption and cronyism are handled, and who essentially is held accountable by law. When you couch these dynamics in an English-centric education system that has always worked closely with the churches, it’s not hard to see how certain historical forces have shaped both attitudes and institutions. It’s also apparent that they still sway what is documented for posterity and the available avenues for change.

I'm extremely grateful that I had the chance to go to Antigua & Barbuda. It is a privilege to be able to travel at all and to have people trust you with their life stories. That said, after this trip, I am left with a number of troubling questions: At this point, who owns Antigua? And what can be done to address the exploitative foreign influences there? Most importantly, how can I, as a descendent of the very white European ancestors who subjugated this island, help raise awareness so that we can stop some of these devastating problems?

I've had the opportunity to see firsthand how enthusiastic citizens are in “developing” countries like Myanmar, where tourism promises new jobs, "stabilization" and an end to sanctions. But I've also witnessed the long-term effects of unheeded "vacationing,” where certain types of tourism become such an ingrained part of the country’s identity and GDP that it becomes impossible to remove them without an economic tailspin. In both, the follow-up responsibilities to protect these beautiful places eventually are at odds with the much-needed revenue streams and means for basic survival. I don't have the answers. And I can't share the faces of some of the storytellers I met this time because the lens I used the most was the one of a white Western camera-wielding guest of the very company that employed some of those who shared their struggles. I don't know if this company, whose natural products are embraced worldwide and who touts a “holistic” image of sustainability, truly understands the extent of how "isolated resort culture," for lack of a better term, dissects and divides the very communities that it is ensconced in.

You don't need to know these things when you visit and, frankly, feedback (both in the U.S. and in Antigua) is not welcome. We go to the beach to leave behind our responsibilities and most travelers don’t want to deconstruct how our shared histories still mold some of these places. We certainly don’t define our ideas about (and language around) private “hideaways/escapes/refuges” to reflect a reality that is more than a falsified notion of ever-present romance that few can obtain and uphold.

I researched the resort more in-depth when I returned to the States and learned that the partnering company who had paid for my room had been sold in 1997, though it is still operating under the same name and affiliations. Coincidentally, the original founder passed away while I was working on this write-up and, with his death, I was able to find out more about what has happened since its inception.

Horst Rechelbacher was an international activist, entrepreneur and health advocate who created cosmetics and beauty services that were safe for the environment. He started the Aveda Institute in 1978 in Minneapolis, Minnesota and this school quickly blossomed into a slew of salons where thousands of top professionals still receive “holistic training.” In 1997, he sold his company for $300 million to Estee Lauder, one of the most well-known and celebrated businesswomen in the world. She went on to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2004, the highest civilian award in America for individuals who make "an especially meritorious contribution to the security or national interests of the United States, world peace, cultural or other significant public or private endeavors.”Eight years later, when Horst’s non-compete agreement with Estee Lauder ran out, he started a certified supplement and beauty product company called Intelligent Nutrients. In this new position, he worked with the United States Department of Agriculture to create food-grade government regulations so that harmful ingredients in cosmetics could not be “greenwashed,” or falsely labeled as “organic.” He ended up using his profits to fund plant cell research, which coincidentally thrust him into a consultant role for the world-renowned Mayo Clinic and other prominent universities and hospitals.

From everything I’ve read, Horst believed in result-oriented success. He was hands-on, creative, and not afraid of messy politics. He traveled incessantly and learned from indigenous peoples in their local environments. He also passionately campaigned against the use of pesticides and other killing agents in order to protect biodiversity.

He was both a teacher and a student in his innovative approach and a trailblazer in how he solved problems. He led by example, living on a farm powered by solar energy, and strongly believed that businesses should be more “response-able” to the communities they serve. Authenticity was his signature and he fervently supported the informed and cooperative purchasing power of his customers. I buy Aveda products on a regular basis because I believe in Horst’s original vision. As a long-term investor, I think it is vital that we respond to requests for comprehensive analysis and public reporting. Industries that embrace the Ceres guidelines are recognized through incentives and awards for following set performance criteria. When new information arises that sheds light on how these corporations can run better, feedback is supposedly welcomed since open discourse is a vital part of what defines accountability.

Conservation means protection of fauna and flora, yes, but it is also based on an in-depth understanding of how the particular ingredients fit into the larger habitat. (i.e. how the goods and services impact those who both cultivate and use them.) Since restoration is another strategy that Ceres highlights, this means addressing where the current blueprint may have failed.

It’s not that we as consumers expect perfection and I applaud any business today that vows to voluntarily go beyond the minimum requirements of the law. It is important to note, however, why these inconsistencies are so troubling in this specific setting.

The Antiguan government is desperately trying to expand their National Sustainable Plan so that businesses that impinge upon the environment through tourism can help set up the necessary frameworks to manage any negative effects. Shared input from the numerous hospitality enterprises then is of dire importance since tourism, directly and indirectly, was estimated to make up between 50% and 70% of Antigua’s GDP in 2007.

Imagine what would happen in Antigua if a behemoth like Estee Lauder Companies, whose total assets were worth $5.18 billion in 2009 (and who still publically “strive(s) to set an example in leadership and responsibility”) were to take on a greater role in cooperating with some of the local activists and other hospitality giants there. Through Aveda, Estee Lauder has already helped to finance various environmental and cultural campaigns in many other countries, as well as outreach programs and eco-friendly facilities. The new Light the Way collaboration with Global Greengrants Fund, for example, supposedly gives 100% of the proceeds for Aveda candles to clean water projects in India. Such efforts in Antigua would, therefore, not be entirely outside of their scope.

The SIDS 2014 Preparatory Progress Report from the Ministry of Agriculture, Housing, Lands and the Environment notes that “the implementation of new policies, technology and infrastructure requires financial assistance beyond the scope of the national economy.” Since the Antiguan market is now so dependent on foreign-run tourism, it is quite conceivable that this acknowledgment could be perceived as encouragement for outside companies to be more active with their local partnerships. In Aveda’s case, Ceres also supports bridging disparate stakeholders with public interest groups.

Under such auspices, Aveda could conceptually network with other private companies and local businesses to influence the government to meet shared target goals. These partnerships could then lead to new environmental standards, legislation and relationship structures, which, in turn, could considerably change how tourism is set up there.

Even for those companies who strive to be “eco-friendly,” the putative motivation and bottom-line concern for any business is profits. As an investor then, I not only support their mission, but understand its relationship to their economic priorities. Aveda’s clients choose these products over other cosmetics, however, because they believe in the company’s integrity and want to give back. In line with this, they want to understand and witness firsthand how their support of Aveda’s alliances are reflective of this same paradigm.

I won the hotel stay because I participate in their long-term fiscal reward system where they honor both their returning customers and their partnerships abroad through accrued points from the purchase of their products and services. At this writing, I have almost enough points to obtain another “free room.” Therefore, it is quite conceivable in my lifetime that I will have the opportunity to return to Antigua. It is my hope that, if this happens, I will be able to see some changes in the ways the hospitality empires are being structured and, with Aveda, whose name literally translates in Sanskrit to mean “all knowledge,” hopefully taking back the lead. Note: You can help support environmental change in the hospitality industry in the West Indies by pushing for more local representation in regulating bodies like the Caribbean Environment Programme or The Small Island Developing States or by contacting umbrella organizations like The International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

© Amy Siqveland May 2014

www.amysiqveland.com

*There is no British High Commission in Antigua and Barbuda. If you need consular assistance, contact the British High Commission in Barbados.**The hurricane season in Antigua and Barbuda normally runs from June to November. See Hurricanes